-

Focusing on a series of migrant experiences in London, I seek to explore the complexities of being ‘out-of-place’, and the experience of setting up a ‘home’ outside of one’s homeland. My research involves my photographing the interiors of their newly established homes, both in relation to their experience as displaced persons, and in the way a domestic space is set up (with particular focus on the ways in which visual imagery and cultural icons are used in a private context) as representations of their identities and sense of cultural belonging. In turn, however, my photographic work implicates the way the photograph becomes part of a complex series of constructions which raise questions about private terms of reference, of space, and interpretation. In these terms, the images depicted raise questions about their anthropological terms of reference and the ways in which meaning is both relative to and dependent upon the specific context in which the photograph is made, read and used. Hence the significance of the migrant experience in relation to the making of meaning out of displacement, and the re-construction of ‘home’ based on this strange, split experience.

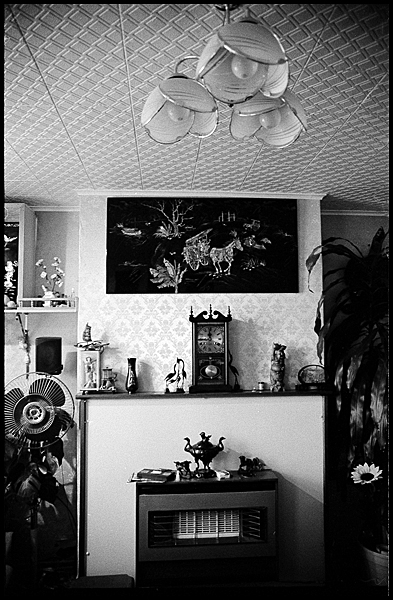

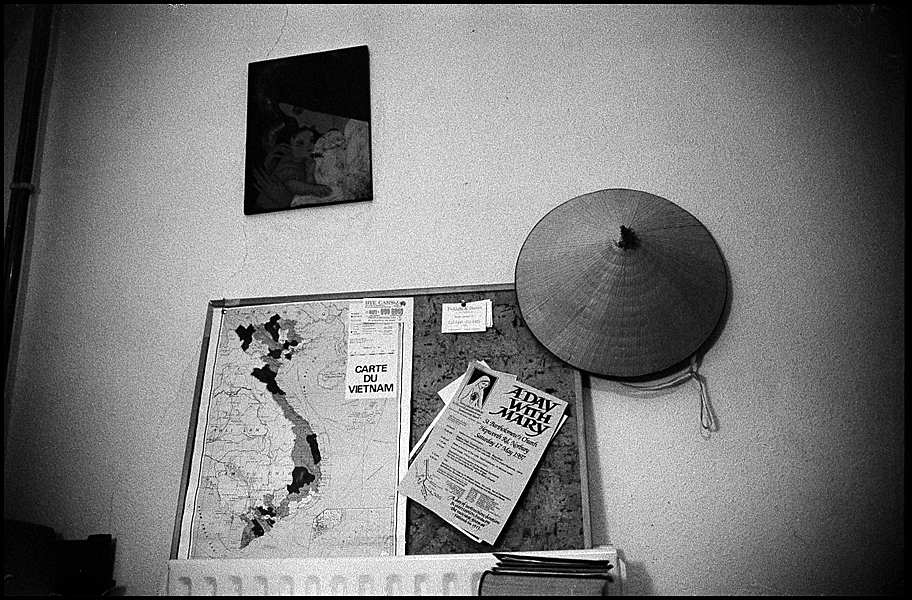

The paraphernalia of the domestic environment, its décor and design, serves the function of describing not only the functionality of one’s domestic environment, but it also reflects a space of longing and presents the possibility of belonging. In this way, perhaps the dislocating effects of forced migration may not only be found in images taken in war zones or refugee camps, but in the set-ups of private, domestic spaces.

The ‘making’ of homes entails an interweaving of personal imagination, lived relationships and shaped surroundings. An understanding of home becomes a means for organising the world and orienting our passage through it. Because homes are constructed from material, social, and cultural resources (and are bound up in the relationships which sustain those resources), discourse about the home contains a complex interplay of personal subjectivity and cultural ideal. As Gaston Bachelard proposes, subconscious imagery of home orients being in the world, overlain with codes, experience and practical knowledge acquired in childhood. Therefore, ideas of home find one kind of integration in the practice of everyday life, and another in the very different space and temporality of memories, dreams and emotions (Bachelard, 1958 and 1960). Alison Blunt and Robyn Dowling also describe the home as being both ‘material and imaginative’, a physical and psychological space containing ‘feelings of belonging’ (2006: 22). -

Therefore, objects around the home do not simply function as tools for survival; instead, they reflect the identities and embody the goals and aspirations of the occupants of the household. Living environments, which represent their distinctive trajectories, are created and shaped, cultivated from personal and familial histories, and sense of stability in a social space. As László Moholy-Nagy suggests, in addition to the social, economic, technical and hygienic factors that traditionally govern the building of a house, human beings must also ‘experience space in his home’. Hence, it is not the practical aspects of construction that are significant, but the ‘experience of space, which is the basis of the mental as well as the physical well-being of the inhabitants’. We must therefore regard the home as a flexible and mobile spatial situation, incorporating the rhythms of everyday life, as he considers it to be ‘an organic part of life itself’. (Moholy-Nagy, 1985:309-10). He proposes that interior spaces could perform a more stimulating function than simply protecting ‘dwellers’ from bad weather. Besides the necessity for functionality within the domestic environment, the home should also be conceived as a space which needs to be shaped, as the space that we occupy and inhabit.

According to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Eugene Rochberg-Halton (1981), objects around the home embody goals and aspirations, shaping the identities of those who occupy the home. The presence and display of material objects in private spaces therefore serve as important markers of identity. The principles of arrangement of features and artifacts have been understood as a way of representing and placing the self or the household in the world. Cheang, in her analysis of collecting, refers to its practice as an expression of cultural and psychological desire, and an extension of the relationship between the body and the physical space of the room itself (Cheang, 2001). Within homes of all kinds, the meanings of it are continually redefined as inhabitants commit themselves to the personalisation of their dwelling spaces. The complexities of how individuals make their choices when setting up home environments are resolved differently according to the life situation of the occupants and their aspirations. The photographic images of these interiors have taken as their subject the familiar and the everyday, and at the same time, they reveal particular histories, endowing these spaces with their individual poignancy. -

John Collier’s Visual Anthropology (1967) provides a popular account of how photography can be used within anthropology. The text focuses mainly on techniques to be used in fieldwork, representing ways in which to use photographic, visual communication as a quasi-quantitative tool. However, more recently, issues around the use of photographic representations in social and cultural research concerns the apparent ambiguity of photographs (due to the polysemic nature of visual material), and also highlights criticisms about the subjectivity of the selection process. Sarah Pink, in turn, suggests that it is a positive advantage to allow multiple interpretations instead of attempting to establish truths within a realist paradigm during the collection of data or representation of results (2001). In this context, my photographic work implicates the way the photograph becomes part of a complex series of constructions and interpretations, which involve discussions of the photographic image in relation to memory, nostalgia, and personal experience, aspects which question the usual terms of the photograph’s status as a record of ‘the real’, notably in relation to historical uses of the medium and the documentary tradition.

As part of the research process, the residents of these homes were asked to speak about their experience of living in a foreign land, and to describe what their notion of ‘home’ is. When considering the meanings and experiences of home, significant connections can be made between notions of home and homeland, particularly for exiles and refugees who have been forced to migrate because of war or persecution. While the interiors range from the emptiness of temporary rented accommodation to well-established decorating arrangements, the narratives accompanying each of the photographed spaces serve to offer a context for the reading of the work. Captions, which accompany the images, are extracts of transcripts of interviews with the residents of each home.

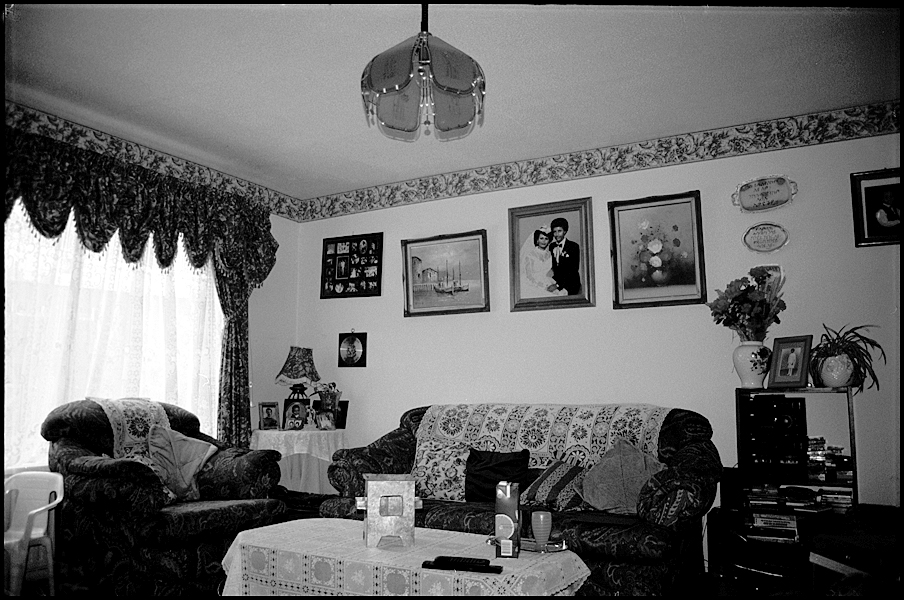

In relation to Figure 1 Elephant and Castle, the mother of my interviewee, a refugee from Vietnam, was chiefly responsible for the ‘look’ of the home; I was told that although she still maintained ties with her homeland (she travels there occasionally), the objects displayed in their living-room served no practical purpose but functioned mainly as symbols of a past that needed to be retained and re-affirmed. His mother’s establishment of the arrangement of the living room and his distance from it reminds us that personal identity in the home is entangled with the individual and collective identity of others sharing the living space. -

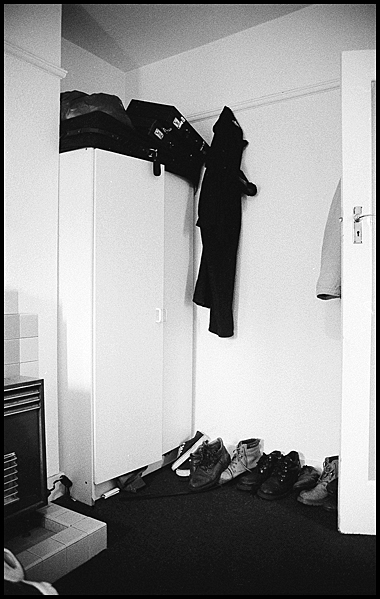

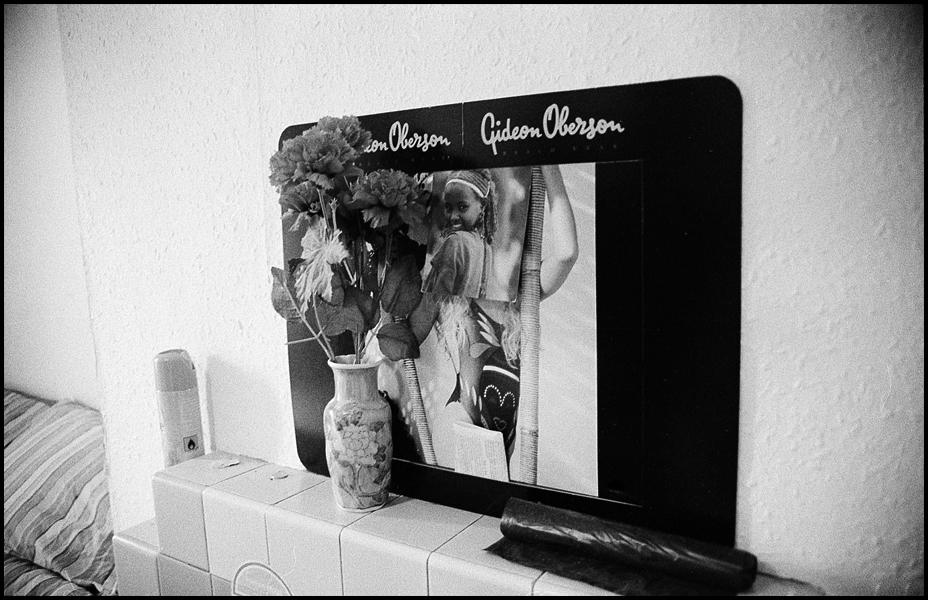

While the first image is filled with a sense of permanence through artifacts and memorabilia of ‘homeland’, Figure 2 Bayswater depicts the sense of transience of a temporary home of a refugee from Berber, North Sudan, who was sharing a rented flat with a friend, intending eventually to move to another flat along Edgware Road. Figures 3 and 4, photographed in Peckham, depict the home of a Vietnamese refugee, a nun who had lived for decades in London and established strong connections with the Vietnamese community in the area.

Figures 5 and 6 Colindale, Northwest London were photographed in the home of a refugee from Khartoum, Sudan. He worked for the Sudanese Victims of Torture Group, a charity organisation based in Clapham, South London. The image of his bedroom containing shoes, jeans, and empty suitcases piled on top of his wardrobe, seemed to typify the migrant’s transient experience, where the luggage stored above functions as a reminder of the repetitious experience of packing/travel/unpacking. The suitcase has come to signify mobility, displacement, and the uncertainty of identities; Irit Rogoff sees the function of luggage as a ‘signification of the ‘degree zero’ of displacement both temporally and symbolically, an originary moment after which all familiarity is lost while change and difference shape life’. (Rogoff, 2000:36) The material possessions that one takes along in the form of luggage, and the travel away from the anchorings of these belongings are crucial to one’s sense of belonging and rootedness. Indeed, forced migration often assumes a form of escape from the homeland, and the residents of these homes describe their inability to take with them many personal belongings (other than photographs) when fleeing in a hurry. Also in his bedroom, was a picture of a Western ‘calendar’ girl in a swimsuit in a tropical beach scene. He had, however, created his own little montage by inserting on top of this European woman’s face, the face of a young Sudanese girl. I was told he did not know this girl personally, but had cropped her image out of a magazine and used it as a substitute for the white woman’s face. -

Figures 7 and 8 depict the living-room walls in a Hammersmith flat inhabited by a refugee from Kurdistan. A framed photograph of a snow-peaked mountain was hung at a height reserved for a sacred object. In the foreground of the image are two very carefully arranged rifles against a mountainous backdrop. She told me the photograph was taken in the mountains where she lived. Brought with them from home, this image represented the KDP (Kurdish Democratic Party) and these were the AK-47 rifles the peshmeghars or Kurdish freedom-fighters used. She first asked if I was familiar with this make of gun, and proceeded to describe to me how to work the Kalashnikov assault rifle, and imitated the sounds the gun makes when fired. A wedding photograph of the interviewee and her husband hung on another wall. It was photographed in the mountains of Kurdistan; she described how they were in hiding at that time, and could not reveal their location even to their families. Personal photographs present a recurring feature in the experiences of forced migration, where images of close family take on an intensified resonance. Indeed, there exists a wide range of research analysing family photographs in relation to memory, personal history and domestic space (such as Hirsch, 1997; Blunt, 2003; Rose, 2003). Figure 9 Wembley belonged to refugees from Eritrea who fostered refugee children. I interviewed the female of the household, whose narrative of dislocation adds poignancy to the ordered arrangement of her domestic space.

-

References

Bachelard, G. (1958) The Poetics of Space, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. First English translation 1964 by The Orion Press, Inc.

Bachelard, G. (1960) The Poetics of Reverie, Boston: Beacon Press.

Blunt, A. (2003) ‘Home and Empire: photographs of British families in the Lucknow Album 1856-7’ in Schwartz, J. and Ryan, J (eds), Picturing Place: Photography and the Geographical Imagination, London: I. B. Tauris, pp. 243-60

Blunt, A. and Dowling, R. (2006) Home, London and New York: Routledge.

Cheang, S. (2001) ‘The Dogs of Fo: Gender, Identity and Collecting’ in Shelton, A. (ed), Collectors: Expressions of Self and Other, London: Horniman.

Collier, J. (1967) Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. and Rochberg-Halton, E. (1981) The Meaning of Things: Domestic Symbols and the Self, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hirsch, M. (1997) Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory, Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press.

Moholy-Nagy, L. (1929), ‘Man and his House’ in K. Passuth ed. (1985), London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

Pink, S. (2001) Doing Visual Ethnography, London: Sage.

Rogoff, I. (2000) Terra Infirma: Geography’s Visual Culture, New York and London: Routledge.

Rose, G. (2003) ‘Family Photographs and Domestic Spacings’, Transactions 28:5-18.

Rose, G., (2007) Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials, 2nd edition, London: Sage. -

Fig. 1 - Elephant and Castle, South-East London

I do not see my family as the typical Vietnamese family. We might keep ornaments in the house to remind us of where we came from, but we are quite isolated from the Chinese community. My mother is still quite religious, by the way. She goes to pray at the temple sometimes… Because I speak with an English accent – I left Vietnam when I was very young and spent the most part of my childhood here – and do not conform to the typical Chinese dress codes, I am often referred to as a ‘banana’. This word is used to describe individuals who look Chinese but whose lifestyle and mannerisms resemble those of a “white” man. I do not have many memories outside this flat. I still feel patriotic about Vietnam. (What do you mean by this?) Oh, I support them in football. I guess although I know more about the U.K. than about the country in which I was born, I am still in some way attached to it; and I would like to go back. Not to live there, just to see what it looks like now... I’m a Vietnamese, and I’m also British. What can I do? I intend to find a job in Graphics, whatever there is available. However, I know I am destined to the wok. Somehow, we always end up opening take- aways wherever we go, and whatever we do. My uncle was a VC, and has two University degrees in Chemistry and Maths, and he’s still making stir- fries here.

-

Fig. 2 Bayswater, London

I still keep strong relations with my country, and would not like to settle here permanently. I miss my family, my sisters and brothers, and the people in my country... I feel completely outside of British culture and way of life. I am still very, very much a Sudanese. When I meet another Sudanese on the bus or on the train, or wave to a fellow Sudanese on the street, I feel immediately close to my people.

-

Fig. 3-4 Peckham, South-East London

The skinheads around here even used to kick pregnant Vietnamese women, and we were always picked on. Nowadays, the Vietnamese girls are much better dressed; they look more modern, and so fit in better. It is also ancestor worship that makes us remain very Vietnamese. It is a very profound practice to respect the dead, respect our roots. Because these are the connecting links to your history, you feel you belong. At the same time, we have photographs and pictures of the dead and also our past. It is good to establish that link to our tradition. So no matter what happens, there will always be something left there.

-

Fig. 5-6 Colindale, North-West London

There are lots of people in my generation who perceive the West is very free – everything is perfect like in the cinema or TV.. the way the media presents them. The image of the West, even the women.. the TV woman.. it is a very ideal world. That’s what I think my perception of the West is.

Many times I embarrassed myself because I discovered that the way I approached girls was not acceptable to people. Sometimes I expect a certain response from my good intentions; and yet I get a negative response. Then I learned to neutralise myself, become more conservative. I became more accepted. It is the opposite in Sudan. People there would think you don’t like them if you behaved that way. It is definitely more individualistic here, and more sense of community in Sudan. -

Fig. 7 - Hammersmith, West London

When I first arrived here, I was happy but not too much. Because when I worked in the mountain ten years ago, I had a very different life. When I worked there, I worked for my people. Now, I just stay at home and look after my baby. But at least I know no one is going to kill me...

-

Fig. 9 Wembley, North-West-WEST London

We were living in the bush all our lives. We were fighting in the bush since 1974, 1975. The Ethiopian government was in control of most of the seats in our government. We were in the bush, you know, just hit and run. That’s where we met… We are stuck between two things. Our heart is always looking backwards. We are torn apart. Our children were all born here, and they don’t want to go back. We don’t want to destroy their future. It is an identity crisis for them. We were members of the Eritrean Liberation Front. I miss my past life so much, especially the way of life because back then, you never know when you are going to die. You don’t owe anybody anything, you have no possessions, you have what your community has and keep a good relationship with others. You don’t know when you are going to die, so you eat for today and you don’t think of tomorrow. Here, nothing is the same or simple as my life in the bush.

Refbacks

- There are currently no refbacks.

ISSN Print 2499-9288

ISSN Online 2281-1605

Publisher Edizioni Museo Pasqualino

Patronage University of Basilicata, Italy

Web Salvo Leo

Periodico registrato presso il Tribunale di Palermo con numero di registrazione 1/2023