-

Joana Roque de Pinho is an environmental anthropologist and postdoctoral researcher at the Center for International Studies (CEI), at ISCTE-IUL, Lisbon (Portugal), and a research affiliate at the Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory, Colorado State University, Fort Collins (USA). At the time of research, she was with the Center for Administration and Public Policies (CAPP), Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Políticas (ISCSP –UL), Lisbon (Portugal). She has conducted research on changing human-environmental relationships among Maasai pastoralists in Kenya and Bissau-Guinean farmers in Guinea-Bissau. More recently, her research has involved engaging members of these communities as co-researchers through participatory visual research methodologies (photography and video).

-

All the images and captions in this photo essay were created by Bissau-Guinean farmers who participated as photographers and researchers in a collaborative research project on local knowledge of climate change. This essay seeks to illustrate the diverse and creative ways in which these West African farmers turned photographers chose to represent the tricky concept of change in its local social, economic, cultural and ecological complexity. [ > NEXT PAGE]

-

The change this research project addressed was climatic change. The goal was to examine how rice farmers living inside Cantanhez National Park in southern Guinea-Bissau perceive climate change, explain it and cope with its impacts on their livelihoods and landscapes. In a context of political economic changes affecting natural resource management and local livelihoods, including increasingly restrictive biodiversity conservation policies (Temudo, 2012; unpublished data, 2011), labor shortage and global commodity prices (Sousa et al, 2014), preliminary exploratory research (unpublished data, 2010 and 2011) had shown land users to be concerned about the loss of one month of rain in the rainy season (June - September/October), increasing weather variability and unpredictability, and increased salinity in the mangrove rice fields (bolanhas) on which numerous households depend. To investigate local perceptions of environmental changes, this research project methodologically involved farmers affected by climatic changes as co-researchers through their use of photography and storytelling – an approach known as participatory photography (Gubrium & Harper, 2013; Pauwels, 2015; Wang et al., 1996; Wang, 1999). [ > NEXT PAGE]

-

These businessmen then have their pictures “washed” (laba, kriol, hereafter, kr.), i.e., printed, in Bissau, the distant capital city. Buying pictures comes at a high price for the customers, who pay a hefty value in advance and sometimes are left empty handed as the pictures they paid for are sold to someone else. Still, notwithstanding these locally condemned unethical practices, pictures of family members, friends and events are cherished by their owners, who fetch them out of locked metal trunks or worn out paper envelopes to display them with pride. Clearly, although the work of these professional photographers was initially not perceived as a respectable activity (i.e., “not real work”) and photography was mostly seen as something brankus (white people, i.e., tourists, NGO staff, scientists) do, these locally produced images are treasured. As their owners explain, they are invaluable records of people and places. And while the scope of photography is locally limited, both in terms of access to cameras and ability to purchase pictures, engaging local farmers as photographers in our collaborative research project was thus not difficult...

PLEASE READ THE COMPLETE INTRODUCTION IN THE PDF FILE -

Abstract

This photo essay, whose images and captions were created by farmers living in Cantanhez National Park, Guinea-Bissau, illustrates and analyzes the diverse ways in which these West African photographers and collaborative researchers chose to represent change. Some of the visual and narrative devices employed by the photographers include staging the past; representing before/after situations; and thoughtful composition in the visual depiction of changed and changing physical environments. Beyond our initial research focus on perceptions of climatic changes, these farmers turned photographers shared compelling portrayals of change in its social, economic, ecological and cultural complexity, in some cases offering counter-narratives to the dominant environmentalist narrative about this protected area.

-

1. Photo by Lissa Turé (41 years old, farmer, palm oil producer)

I took this photo to recall the past. In the past, when my grand-mother traveled, she would take clothes and put them in a calabash that would travel on top of a boy’s head. There were no backpacks at the time. The boy and the grandmother would go bare feet (“with their feet on the ground”: pata na tchon, kr.); and clothes did not have a good quality. That’s why I recalled that time with this image.

-

2. Photo by Bulutna Nancussa (48 years old, farmer)

This is an old water spring. Do you see this boy with the calabash, and his clean feet [i.e., bare feet]? The way he is standing there, inside the spring, with his foot on the ground, he is fetching water to put in that bucket. In the old springs, like this one, people would get in the water, fetch water, and pass the bucket to a companion hauls it up. What made me take this picture is that nowadays we have different water sources. The ones we have now are covered wells.

-

3. Photo by Papis Demba Camará (48 years old, farmer, mason, bike mechanic, former adult education teacher, football referee)

I call this picture “Cafal of yesterday”. The second image is called “Cafal of today”. I took these pictures to record a change. This is the trunk of an old mango tree. In the past, our school was this one [under the mango tree]. This is the school that took our elders to Terra Branku [Europe]. This is the school that helped our elders free this land [Guinea-Bissau; he is referring to the 1963-74 Independence War]. This was their school. If today we see the greatness of this village, it is thanks to this tree and the advices that people received underneath it. All the elements you see in this picture play a role. That elder with the barkafon [a traditional bag] is the advisor. Inside, are his secrets: the pipe; the tobacco container; the palm tree fiber for [spiritual] safety while traveling. The bottle of “that other thing” is also there – I cannot mention its name. The three youth touching the trunk are receiving advice. The man with his hand in the air is calling people. The boy is carrying fire for the elder’s pipe. This is how our elders’ school used to be. This is how people were taught from Class One all the way to Class Seven, here underneath this tree around which people are seated. Many [youth] do not know this school. Under this tree has passed all the population of Cafal. Many elders sat here [he cites five names]. All received teachings underneath it. People also received advice before a journey. When drums were here, everyone from [nearby villages] would meet here. The Portuguese colonial head of administrative post (Chefe de Posto) would collect taxes here. Before, Cafal used to be darker, as this tree was planted in the middle of it. But it was felled [in 2008] because we wanted light. Because of the wind and to avoid darkness, people decided to cut this tree down, and the village got light. This also happened because of another change: cars and motorbikes – to avoid accidents. This changed Cafal’s character. When the mango tree was felled, lots of people cried.

-

4. Photo by Papis Demba Camará (48 years old, farmer, mason, bike mechanic, former adult education teacher, football referee)

Today, we have a new method to teach children. The man with the black pants is the teacher walking his students to school and is looking at a student playing [on all fours]. The man with the white shirt [a student] is advising his colleagues to go to school. Because if they don’t, nothing good will come of it. Thanks to such advice, we now have students graduating in our and other villages. Thanks to this change, things are better. Change your environment. Change even the character of your thoughts so that you know that other things will come. But never forget this is a big change. Take this type of change as an example; come out of the bad things and welcome the good things. The school from the past and today’s school have their differences, but we need to follow both, a little of each. Children’s education starts at home, and then teachers do the rest. This is why I took these pictures, to remind people that there used to be a type of school [under the mango tree] and today we have the schools where pupils sit at desks. -

5. Photo by Bebe Naman (31 years old, farmer)

This is an ancient thing, called ngae, which the Balanta used to do in the past. Today it’s difficult to find people that still put these lianas [malilas, kr.] on. People have changed. They wear good clothes and stroll around. In the past, youth would wear these lianas and would walk shirtless all the way to Bissau. I found this boy on that day, on the eve of his ninth birthday party, and I saw how he was dressed. I was very happy. Today, it is very difficult to find someone going shirtless. I took this picture to show the youth of today this custom that boys no longer do. In the past, this is how our elders would do. Why did this practice diminish? People have become careless. In the past, the majority did not go to school. That’s why today, people want to kill this tradition so that the youth stay in school.

-

6. Photo by Manuel Camará (75 years old, farmer, Independence War veteran)

My comrades, my brothers, my uncles, and my children, I will tell you the story of this motor boat, the first one in Cafine. In the past, we didn’t have such motor boats. We would row all the way to Catió [neighboring peninsula] to take someone sick for treatment. It was very difficult. When there was wind, we would sail. But when the wind disappeared, no one could go anywhere. But today we have development. Motor boats are development. With a motor boat, no one gets tired [i.e., there is no difficulty]. Not unless the engine breaks down. I took this picture to show development, which feeds and helps us.

-

7. Photo by Mussa Conté (44 years old, farmer, bike and motorbike mechanic)

Here was located the first village [tabanca, kr.] of Calaque. During the [Independence] war people lived here. At the end of the war, they moved to a new village. [I took this picture] near an old house. The owner of this piece of land planted these flowers so that his children know that “Our father planted these flowers to show us this is our piece of land”. The father planted these flowers for his family’s future. When this young woman was a girl, the mother took her by the hand [around] her father’s plot: “This is the land of your late father, which was near the house, where these flowers are. You now take care of [it]. This piece of land is yours”. Later on, the young woman can take the hand of her younger brother and show him their father’s plot, identified by the flowers. In the past, our elders would not demarcate their pieces of land. They would simply build houses. But this man thought of his children to come. So he planted these flowers on his plot. Some people would sow kola trees; others, mango or orange trees. Others would sow nothing. In that time, everyone had their own idea. They would think “This is the war, I don’t know if I will make it, why make a plantation?” Even before the war, our elders did not think of doing something for the future. But now we are in the world of development. Every day, things change and this is how the idea of development increases and people are starting to delimit plots for their children. I want to identify my plot of land with cement slabs, with the name of my first son, Mussa. Tomorrow, if I die, my children will have evidence that “this piece of land belongs to our father”. If people do not mark their plots today, tomorrow they’ll have problems. Someone can say “This plot is mine. I had loaned it to your father”. But if I have a mark with my name on it or flowers, I can prove the plot is mine.

-

8. Photo by Pedro Nancussa (70 years old, farmer, Independence War veteran, manager of the mangrove rice fields’ water management system)

In the past, we used to use husk rice with a mortar (pilon, kr.). When the rice was clean, people carried it inside that basket (kufo, balanta). My grandmother and my mother worked like this until they died. Our elders had no other way of doing it. This is the only way they had to husk rice. It is extremely difficult for women. I took this picture among traditional houses to show this is in the past. Now (2nd image), change has come. Difficulty (“fatigue”: kansera, kr.) is over. If someone has 10 bags of rice, they can take it to the husking machine and the rice gets husked in two hours. -

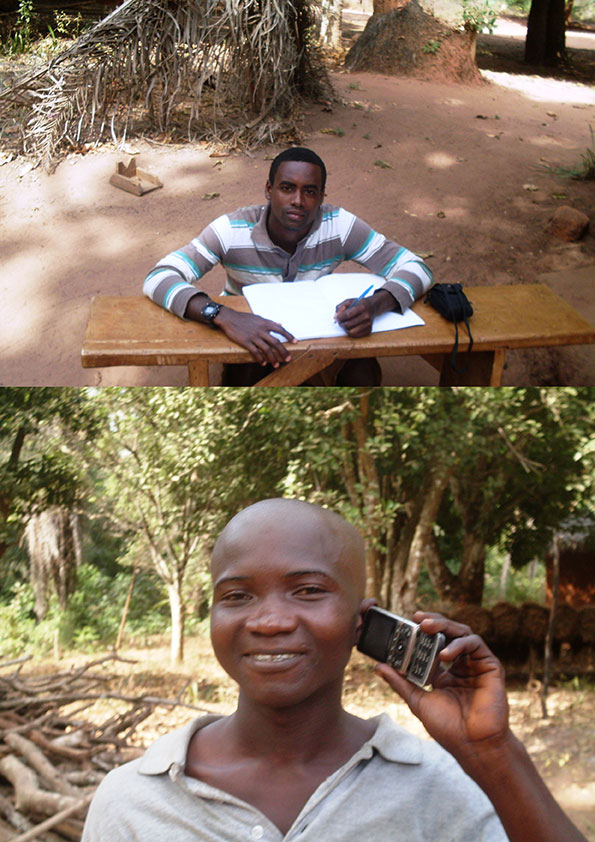

9. Photo by Sene Cassamá (36 years old, farmer)

This (first image) is a story from the past. In the past, if you wanted to talk with a family member, you had to write and send a letter. But the person to whom you gave your letter might not find the recipient. Or the letter would stay in their hands for months and wouldn’t find its owner. And the family would be worried. In the second image, we have a cell phone. Since cell phones exist, the whole world is relieved. Today, someone might be in Portugal and they can talk to their family. Even money can be transferred by cell phone. You can send letters [SMS messages] by cell phones. [The time of paid] radio messages informing someone that a letter was on its way and that used to reveal people’s secrets is over. Everyone, even in other countries, would know what the letter said. Now, this is over, we’re in the phase of development. I give you money for you to give my brother. Before you get there, I inform my brother [that you’re on your way], to make sure you don’t misbehave.10. Photo by Bebe Naman (31 years old, farmer)

I’m the one who took this picture. This is the bolanha (mangrove rice field; kr.) of Cadique-N’bitna. In the past, all of this was cultivated. But now it’s all damaged and abandoned because (sea) water came from the river and destroyed the dikes [in 2008]. The main dike (dique de cintura; Portuguese) was close to the river, and it broke first. Then the other dikes lost their support and also broke down. Only that bridge that we see over there remained, where people still cultivate rice. Over there, they are restoring the bolanha. This is a change. My family is there. They were affected, they’re suffering, they now have fewer cultivated parcels. People want to restore the bolanha and rebuild the main dike over there. Right now, people depend on cashew. They collect the nuts and trade them for rice.11. Photo by Albat Ialá (29 years old, farmer, primary school teacher, secondary school student)

In the past, this pond was good. Our cows used to drink there. I took this picture to show that cows cannot drink there now because sea water got in there and the cows feel bad. Before, we didn’t worry about water for cattle. But in the past four years, it’s been a great source of worry because sea water has invaded this drinking place. It’s a negative change. That’s what motivated me to take this picture; to show the youth that this is not how this pond used to be. A high tide [yagu sin bibu, kr. – literally, water that leaves no one alive] damaged it. Underneath those rocks are freshwater springs and crocodile (lagartu, kr.) holes. One day, an elder found a baby crocodile and placed it in this pond. The crocodile grew up, then went to the river to get married and had many children here. People wanted to kill these crocodiles but the elders didn’t allow it. These elders had adopted these crocodiles like people in India have adopted the cow. One day, when the water was dirty, we went to clean the water springs, we found a crocodile in its hole. We had wanted to kill it but the elders stopped us: “You grew up and found this crocodile. It is not for you to kill it”. […] When I saw this picture on my camera’s screen, it was a surprise to see the trees reflected in the water! The sun was going down. I didn’t know that the trees would come out like this, in the water…12. Photo by Mussa Conté (44 years old, farmer, bike and motorbike mechanic)

This is a lala (a humid savanna) and this grass is karatá [a valuable roof thatching resource]. On the left is the forest. On the right is the mangrove. Today, the forest is coming in and taking the lala over and so the lala is getting finished. The mangrove is linked to the forest because the river has entered all the way to the forest. The forest and the mangrove are coming together to finish the lala. It’s fresh water that has brought the forest. The land here has a slope. So, during the rainy season, water comes down from the village and accumulates here. With the entry of freshwater, the lala has lost its strength. Water always helps the trees. When it rains a lot, fresh water increases. But when there is little rain, fresh water decrease […]. In the past, it used to rain a lot. But now rain varies: one year it rains a lot; another year, rain is little. One year, it may rain for only two months, August and September; another year, it may rain from May to October. In the past, it rained so much that houses fell down. It no longer happens.13. Photo by Paulo Nanfuta (34 years old, farmer)

This trunk belongs to a polon (kr.; silk cotton tree or Ceiba pentandra; a forest tree) that was cut down more than two years ago and died like this. Another polon, a little polon, was born inside the trunk of the dead polon. It’s the owner of the big polon, who had cut it down, who sowed the little polon inside the trunk of the old polon. The dead polon’s trunk allowed this change to happen: it had rotten and the little polon was sown inside of it and then it grew. These are two varieties of polon: one is reddish; the other one is bright yellow.14. Photo by Haruna Cassamá (33 years old, farmer, mason, carpenter, auxiliary nurse)

I took this picture in Calaque, in the orchard of a man called Umaro. There are six silk cotton trees (polon, kr.; Ceiba pentandra), which were planted. The first day I went to this place, I saw three polon on one side and three polon on the other side. I wondered about this as I didn’t know that these polon had been sown. The garden’s owner explained: “These polon were planted by my grandfather because he thought that in the future they might have value”.15. Photo by Papis Demba Camará (48 years old, farmer, mason, bike mechanic, former adult education teacher, football referee)

This is a cibe (Borassus aethiopum; a wild palm tree) plantation. Before, this was a rice nursery. The rice seedlings would be transplanted to the bolanha [mangrove rice field]. More than 10 years ago, the owner of this plot realized his land was degraded. So he had the idea of planting cibe, thinking that one day it would be worth money. He brought cibe seeds from a neighbor’s plot and sowed it. This is how he managed to obtain a cibe plantation of this size. He discovered the value of cibe after traveling to Quínara and seeing that one cibe tree is worth CFA 10000 [EUR 15]. If it is felled and divided in boards, each boards costs CFA 500 [EUR 0.76]. Seeing that this is something that is very valuable, he decided to experiment and plant cibe on his plot. He is the first person in the region to do it, and without any NGO support. His children water the trees. This is a beautiful change because the land owner changed his land several times. It has been a clean space, with nothing, no trees, no grass, a rice field dominated by sand [erosion] - you can still see the parcels and the dike. Then the owner transformed that land into a rice nursery. Then he had wanted to make it a palm tree [Elaeis guineensis; for palm oil production] nursery. But when he discovered the value of cibe, he decided to experiment with it.16. Photo by Sene Cassamá (36 years old, farmer)

What we see here is the former store of Calaque. When I was born, I found stores like these in all the villages. Everyone would go to this store in Calaque to sell and buy things. This store even bought palm kernel oil. People would take their products there, like palm oil, for the store to buy and sell. Then after its owner’s death in 1999, the store was abandoned. Behind this store was located the old Portuguese store, the Casa Gouveia. The manager of that store planted these coconut trees. It’s a big change, this place is damaged now.17. Photo by Haruna Cassamá (33 years old, farmer, mason, carpenter, auxiliary nurse)

I got this story through my father. Cafal started here. The person who discovered this place was Manuel Camará’s grandfather [a 75 year old project photographer], called Torongos Camará. He used to live in Calaque and was a great hunter. While hunting, he arrived here, well before these planted mango trees existed. Nowadays, there are mango trees, and kola trees. Torongos returned to Calaque and told his neighbors: “I found the place that I want to settle”. There was no road to there at that time. Torongos was the first to build his home here. After his family increased, people from Cafal moved to the low lying area, to get closer to the bolanha [mangrove rice fields]. This used to be a village; now it’s almost forest. It’s a good change because we got out of the forest and settled closer to the [new] road.Refbacks

- There are currently no refbacks.

ISSN Print 2499-9288

ISSN Online 2281-1605

Publisher Edizioni Museo Pasqualino

Patronage University of Basilicata, Italy

Web Salvo Leo

Periodico registrato presso il Tribunale di Palermo con numero di registrazione 1/2023